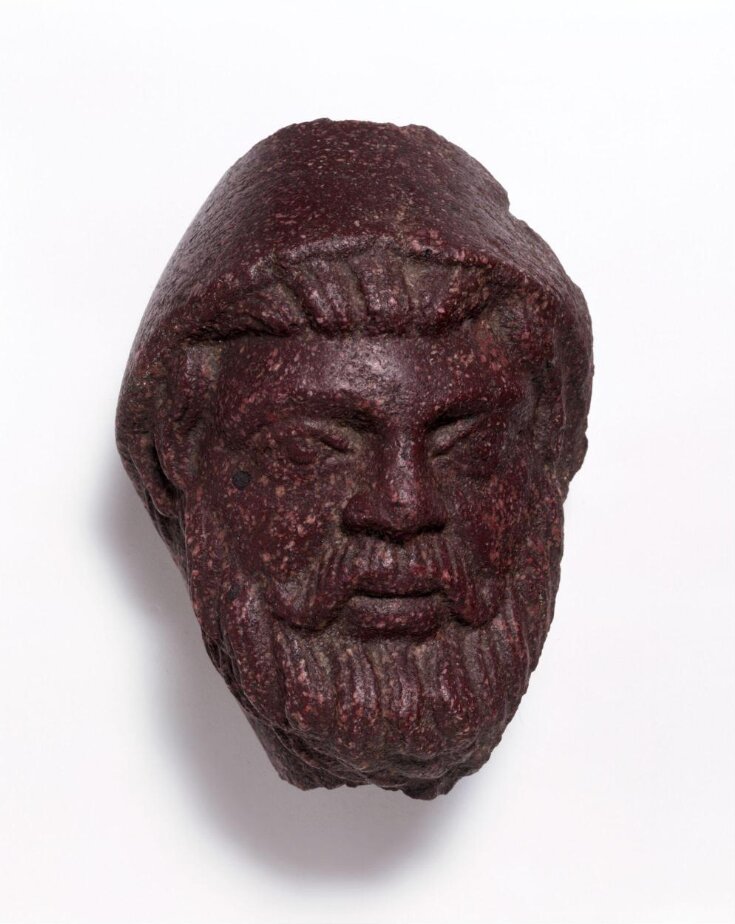

Head of a Warrior

Head

300-400

300-400

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

This head represents a Goth or Persian warrior. It may come from the sarcophagus of St Helena, mother of Emperor Constantine, which is preserved in the Vatican. Because of its purple colour, porphyry was used both for statues depicting the imperial family and for their sarcophagi.

The site of the ancient porphyry quarries from which this stone originates, after being long lost, was discovered in the Nineteenth century by Burton and Wilkinson at Gebel Dokhan, situated in the Red Sea mountains of eastern Egypt. The purple Imperial Porphyry is found nowhere else in the world, except in these mountains (together with other types of Porphyry) and the Romans went to extraordinary lengths to acquire substantial amounts of it. The environment around the mines was harsh with little readily available water - the present day climate can reach 114 degrees Fahrenheit and there would have been no local source of food with wildlife extremely scarce. The extraction of porphyry from this inhospitable terrain was a considerable logistical feat. The material could only be extracted in workable blocks from the tops of four mountains, from whence it was transported down narrow zig zag paths and slipways which are still preserved. On reaching the wadi bed the archaeological evidence of the transportation continues in the form of a cistern and animal lines and then a great loading ramp 8km futher on, where it is believed the the stone would be loaded on to carts for the journey to the Nile, 150km away, going via Badia on a road delineated by cairns that are still visible today. The site of the mines was explored and excavated by a team lead by Dr Peacock of Southampton University in the Imperial Porphyry Mines Project.

The site of the ancient porphyry quarries from which this stone originates, after being long lost, was discovered in the Nineteenth century by Burton and Wilkinson at Gebel Dokhan, situated in the Red Sea mountains of eastern Egypt. The purple Imperial Porphyry is found nowhere else in the world, except in these mountains (together with other types of Porphyry) and the Romans went to extraordinary lengths to acquire substantial amounts of it. The environment around the mines was harsh with little readily available water - the present day climate can reach 114 degrees Fahrenheit and there would have been no local source of food with wildlife extremely scarce. The extraction of porphyry from this inhospitable terrain was a considerable logistical feat. The material could only be extracted in workable blocks from the tops of four mountains, from whence it was transported down narrow zig zag paths and slipways which are still preserved. On reaching the wadi bed the archaeological evidence of the transportation continues in the form of a cistern and animal lines and then a great loading ramp 8km futher on, where it is believed the the stone would be loaded on to carts for the journey to the Nile, 150km away, going via Badia on a road delineated by cairns that are still visible today. The site of the mines was explored and excavated by a team lead by Dr Peacock of Southampton University in the Imperial Porphyry Mines Project.

Object details

| Category | |

| Object type | |

| Title | Head of a Warrior (generic title) |

| Materials and techniques | Carved Porphyry |

| Brief description | Head, porphyry, head of a warrior, Italy, 300-400 |

| Physical description | The head of a warrior turned to the left. the warrior wears a conical helmet, is bearded and moustached. carved in light reddish-purple porphyry, the head appears to be a fragment of a monument in high relief. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Credit line | Given by Dr W.L.Hildburgh L.F.S.A. |

| Object history | The head is definitely from a relief, probably the sarcophagus of St Helena in the Vatican. Bequeathed to the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1956 by Dr W.L.Hildburgh. Historical significance: A footnoted comment in The Triumph of Vulcan (p.119) claims that it took twenty five stone cutters nine years to clean and restore the sarcophagus of Saint Helena in the Nineteenth Century, a testament to the difficulty of working with this material. |

| Historical context | An engraving by Piranesi (Antichita di Roma, III pl.19) shows that prior to restoration in the 18th century, the sarcophagus of St Helena was in a highly dilapidated condition, with most of the heads and legs of the warriors and horses, having been broken off. The subject was probably intended to represent a Goth or a Persian, the type is very much that of a barbarian. A head, very close in style and scale, also considered to be from the sarcophagus and currently in the Vatican, is illustrated in R.Delbruek, Antike Porphyrywerke. When both heads are measured from brow to beard tip, head A.102-1956 is the greater by only 0.1 cm. Five other warrior heads are known, three in the palazzo Riccardi, one in the Museo Archaeologico, Florence, and one in the collection of Ince Blundell hall. The measurements of these heads range from 10.5 to 18 cm and and may not be from the sarcophagus, but may be of the same date. A similar porphyry head in the Walters Gallery in Baltimore is now considered to be a fake. The sarcophagus was probably intended for Constantine himself (Krautheimer, Rome, p.213). According to Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus, Constantine the Great and Saint Helen were buried in a different porphyry sarcophagus facing east in the Constantinian mausoleum attached to the church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople (R.Gnoli, Marmora p.85). The site of the ancient porphyry quarries from which this stone originates, after being long lost, was discovered in the Nineteenth century by Burton and Wilkinson at Gebel Dokhan, situated in the Red Sea mountains of eastern Egypt. The purple Imperial Porphyry is found nowhere else in the world, except in these mountains (together with other types of Porphyry) and the Romans went to extraordinary lengths to acquire substantial amounts of it. The environment around the mines was harsh with little readily available water - the present day climate can reach 114 degrees Fahrenheit and there would have been no local source of food with wildlife extremely scarce. The extraction of porphyry from this inhospitable terrain was a considerable logistical feat. The material could only be extracted in workable blocks from the tops of four mountains, from whence it was transported down narrow zig zag paths and slipways which are still preserved. On reaching the wadi bed the archaeological evidence of the transportation continues in the form of a cistern and animal lines and then a great loading ramp 8km futher on, where it is believed the the stone would be loaded on to carts for the journey to the Nile, 150km away, going via Badia on a road delineated by cairns that are still visible today. The site of the mines was explored and excavated by a team lead by Dr Peacock of Southampton University in the Imperial Porphyry Mines Project. The Egyptians had first quarried and carved hard stones in the Eastern Desert of Egypt, however very little porphyry appears to have been used until the Ptolemaic period (circa 305 BC - 30 BC). Those who worked porphyry during the Roman empire continued to use the proven Egyptian methods of carving hard stone - the techniques of pounding the stone with other hard stones and soft metals to break up the softer matrix and release the hard crystals within to wear down the surface before finishing with a process of grinding and abrasion (A.Lucas ancient Egyptian materials and industries). The Romans were however also able to benefit from the sophisticated iron and steel industry which they acquired as their territorial control of Europe expanded including: Celtic techniques and hard steels from Spain and Noricum which would have enabled the virtuoso effects achieved in some statuary. (R.J. Forbes - Metallurgy in Antiquity, Leiden 1950). The works produced in the Roman period, tended to be of extremely high quality and constitute one of the more original aspects of the art of the time. A high proportion appear to have been imperial commissions for major public monuments in Rome, for the great imperial palaces in and around the city, or for imperial benefactions elsewhere. The emperors, who owned and operated most of the quarries and thus presumably had first call on available supplies, may have exercised their rights still further in order to restrict access to others, turning all large scale statuary in coloured stones into a particular symbol of imperial prestige. (Grove) Porphyry is composed of crystals of white or red plagioclase felspar, embedded in a fine red ground-mass consisting of hornblende, plagioclase, apatite, thulite, and withamite, the last two being bright red in colour. The overall effect of the rock's geological composition is a redish-purple colour which takes a high polish. This imperial colour made it particularly appropriate for the draped statues of the goddess Roma (such as that found at Cori, now displayed in a niche at the Palazzo Senatorio, Rome) and emperors wearing the toga, whose head and exposed arms were inserted in white marble. The emperors of the late Empire (such as Diocletian and the Tetrarchs, Venice) sometimes had themselves portrayed completely in red porphyry and some (Constantine) were buried in red sarcophagi. Through imperial use, porphyry became imbued with an enduring association with power, and continued to exercise symbolic influence throughout the medieval period (see Hildesheim portable Altar 10-1873) and the Renaissance (see relief of Cosimo I de' Medici 1-1864). The Quattro Santi Coronati or Four Crowned Martyrs were porphyry carvers, probably condemned to work in the imperial mines for the Emperor Diocletian (A.D. 284-305). Their stonecutting comrades found their own hardened chisels shattered when they attempted to carve the stone while the four Christians, with tools mysteriously tempered by Christ carved all manner of requests. Their downfall came when they refused to carve a simulacrum of the Greek God Aesculapius for the Emperor and were consequently incarcerated in lead coffins and thrown into a river. These porphyry carvers were to become the patrons of the Guild of stone and wood carvers, The Quattro Santi Corronati for which Nanni di Banco carved their likeness in the fifteenth century. (S.Butters Triumph of Vulcan) |

| Production | Roman |

| Subjects depicted | |

| Summary | This head represents a Goth or Persian warrior. It may come from the sarcophagus of St Helena, mother of Emperor Constantine, which is preserved in the Vatican. Because of its purple colour, porphyry was used both for statues depicting the imperial family and for their sarcophagi. The site of the ancient porphyry quarries from which this stone originates, after being long lost, was discovered in the Nineteenth century by Burton and Wilkinson at Gebel Dokhan, situated in the Red Sea mountains of eastern Egypt. The purple Imperial Porphyry is found nowhere else in the world, except in these mountains (together with other types of Porphyry) and the Romans went to extraordinary lengths to acquire substantial amounts of it. The environment around the mines was harsh with little readily available water - the present day climate can reach 114 degrees Fahrenheit and there would have been no local source of food with wildlife extremely scarce. The extraction of porphyry from this inhospitable terrain was a considerable logistical feat. The material could only be extracted in workable blocks from the tops of four mountains, from whence it was transported down narrow zig zag paths and slipways which are still preserved. On reaching the wadi bed the archaeological evidence of the transportation continues in the form of a cistern and animal lines and then a great loading ramp 8km futher on, where it is believed the the stone would be loaded on to carts for the journey to the Nile, 150km away, going via Badia on a road delineated by cairns that are still visible today. The site of the mines was explored and excavated by a team lead by Dr Peacock of Southampton University in the Imperial Porphyry Mines Project. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | A.102-1956 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | February 2, 2006 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest